Some distilleries find inspiration in nature. Others look to their own heritage. For New Hampshire’s Tamworth Distillery, terrain and tradition play equal roles in the making of their small-batch products—testaments both to old-timey, forgotten recipes, and to the natural bounty found in their surroundings.

Tamworth Distillery in New Hampshire. All photos courtesy of Breanne Furlong.

Tamworth Distillery in New Hampshire. All photos courtesy of Breanne Furlong.

At a glance, the place seems like it’s been there for decades: a pastoral, renovated inn in a tiny town amidst New Hampshire’s White Mountains. In fact, the distillery was opened just a year ago by former advertiser Steven Grasse, who dreamed up both Sailor Jerry’s Rum and Hendrick’s Gin. His most recent project, Art in the Age of Mechanical Production, is a range of artisanal spirits inspired by long-lost recipes in American history: root liqueur modeled after circa-1700’s “root tea”; a ginger and molasses spirit that hearkens back to the Pennsylvania Dutch. Tamworth is where those spirits (among others) are conceived and produced.

All of Tamworth’s grains are sourced from within a 150-mile radius from the distillery, and many of their botanicals are from nearby farms (or the distillery’s own garden).

All of Tamworth’s grains are sourced from within a 150-mile radius from the distillery, and many of their botanicals are from nearby farms (or the distillery’s own garden).

After being used in distillation, many botanicals are repurposed into jams, infusions, granola bars, and other products.

After being used in distillation, many botanicals are repurposed into jams, infusions, granola bars, and other products.

Words like “small batch” and “grain to glass” are seemingly ubiquitous among today’s crop of craft distillers, and Tamworth takes this same approach. The distillery prides itself on being a true farm-to-bottle company: all of the grains they use are GMO-free and sourced from within a 150-mile radius of the distillery, and most of the botanicals are collected from either the distillery’s own garden, or from neighboring farms. Tamworth also repurposes its ingredients once they’ve served their duties in the distillery, making cattle feed from spent grain and granola bars or jams from other botanicals. The quality of their ingredients is clearly a priority, and that goes for the water, too—Grasse says he chose New Hampshire mostly because the state’s unique geology will never allow fracking, ensuring consistently pure, untainted water (sourced from the nearby Ossipee Aquifier).

The grains, all of which are sourced from within 150 miles, are repurposed into cattle feed after distilling.

The grains, all of which are sourced from within 150 miles, are repurposed into cattle feed after distilling.

Founder Steven Grasse chose to open Tamworth in New Hampshire for the purity of the state’s water.

Founder Steven Grasse chose to open Tamworth in New Hampshire for the purity of the state’s water.

Inside the distillery, visitors will easily spot Tamworth’s gleaming 250-gallon copper still. It was custom-made for Tamworth by the renowned Vendome Copper and Brass Works, a fourth-generation family company and one of very few U.S.-based copper fabricators making stills today. The distillery’s 300 barrels are housed in a building that once housed a boxing ring (the balcony seats are apparently still visible) and a dentist’s office. A recent release was named after an eighteenth-century German naturalist, and others cite the likes of twelfth-century German monks and Thomas Jefferson’s botanist among their influences. It’s safe to say that this place runs on history—though with a fully functioning test kitchen and a very active imagination, only time will tell what sort of unlikely creations Tamworth’s distillers might have in their future.

The barrelhouse at Tamworth was once home to the village’s prizefighting ring.

The barrelhouse at Tamworth was once home to the village’s prizefighting ring.

The 1,300-square foot distillery uses a 250-gallon copper still made by Kentucky’s Vendome Copper and Brass Works, a fourth-generation family business.

The 1,300-square foot distillery uses a 250-gallon copper still made by Kentucky’s Vendome Copper and Brass Works, a fourth-generation family business.

Tamworth’s other distillery equipment includes a Scotch-style brandy helmet, a whisky column, a gin basket, four fermenters, six holding tanks, a hot water reclaiming system, and a mash cooker.

Tamworth’s other distillery equipment includes a Scotch-style brandy helmet, a whisky column, a gin basket, four fermenters, six holding tanks, a hot water reclaiming system, and a mash cooker.

Tamworth Garden Apiary Gin, a gin slightly sweetened with local honey, and Eau De Vie, an unaged apple brandy.

Tamworth Garden Apiary Gin, a gin slightly sweetened with local honey, and Eau De Vie, an unaged apple brandy.

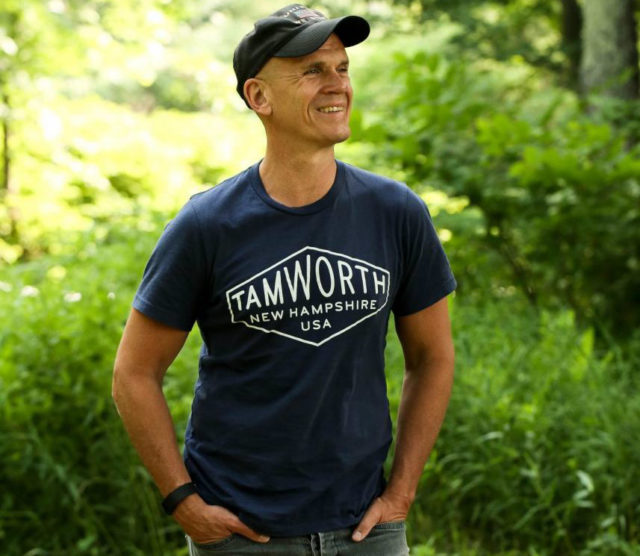

Steven Grasse, founder of Tamworth Distillery.

Steven Grasse, founder of Tamworth Distillery.