Gum syrup. Gum arabic. Gomme. Whatever the name, the prominent pre-Prohibition bar ingredient is making a resurgence and being deployed at many finer cocktail establishments across the country.

“As the ‘geeky’ bar community has grown, a lot more people in the industry are aware of what these ingredients are,” explains Jennifer Colliau of Small Hand Foods, a purveyor of cocktail ingredients including several different gum syrups.

The Rise & Fall of Gum Syrup

Originally, gum syrup was as a true bar staple, with a near omnipresent status. “It shows up in just hundreds of those old cocktail recipes,” says Matthew Rowley, author of “Lost Recipes of Prohibition.”

Beyond its usage in cocktails, it was also used in a slightly different fashion as well, helping customers wash down some of the very bad and very common fake whiskey of the pre-Prohibition days. “Depending on who you talk to, something like 80 or 90 percent of whiskeys on the American market were complete fakes before 1906,” explains Rowley, citing the year when the Pure Food and Drug Act went into effect.

“You put down a bottle of whiskey and a bottle of gum and you let the customers serve themselves,” he says. “If all of your whiskey is kind of crappy and harsh, you want that to not just provide mouthfeel, but also soothe it and make it more palatable and pleasant to drink.”

That mouthfeel though is the key to gum syrup, and it’s made possible by its characteristics as a hydrocolloid. “Gum arabic helps to keep essential oils or other flavors in suspension,” explains Rowley.

“I use organic sugar in my gum syrup, which adds a light molasses flavor,” says Colliau. “But the gum arabic has very little flavor itself. Gum is really all about adding viscosity to drinks.”

At Betony in New York City, the bar produces their own housemade gum syrup.”Gum syrup has a very mild flavor that integrates subtly in a cocktail,” says general manager Eamon Rockey.

Betony’s Pisco Sour uses gum arabic to create and maintain the ideal smooth and velvety texture.

Betony’s Pisco Sour uses gum arabic to create and maintain the ideal smooth and velvety texture.

“Texture is certainly the quality predominately desired. It’s a common misconception that gum creates more foam in egg white cocktails. In reality, the volume is slightly diminished, but the foam itself is thicker and degrades more slowly, resulting in enjoyable smoothness that lingers to the last sip.”

Clearly, the gum syrup which was passed on through the generations was all about texture. Talk to anyone who’s familiar with gum syrup and its applications behind the bar, and inevitably, words like “smooth,” “velvet,” and “silky” will come into play.

Yet, that wasn’t always purely the case. “Almost every single bartender is making it wrong,” Rowley says with a chuckle. “At least, what they’re making as gum syrup is not what was gum syrup before the late 19th century.”

Going back to recipes from the 1830s and earlier, there was another key ingredient — sweet almonds. “If you look at the old recipes, they almost all include almonds,” says Rowley. “I’ve yet to see somebody making gum arabic syrup with almonds the way it’s supposed to be done properly.”

That’s due to how it was popularized. Gum syrup gained more mass appeal with Jerry Thomas’s seminal “Bar-Tenders Guide: How to Mix Drinks” in 1862, and later through other texts, such as Charles Baker’s “The Gentleman’s Companion from 1939.” Yet, even by Thomas’s era gum syrup had already fundamentally changed. “By the time Jerry Thomas is writing about it, we lost the almonds already,” explains Rowley.

By the time Baker gets to it, there isn’t even gum arabic used in gum syrup. “It was expensive and difficult to make,” says Colliau, “and ultimately bartenders dropped the gum in favor of straight simple syrup, although many continued to refer to it as such.”

Despite its original popularity, by the time Prohibition came and went, gum syrup disappeared entirely. “Prohibition killed the cocktail in many ways,” says Rockey. “The accessibility of soda guns and sour mixes killed fresh citrus, and low quality ice changed the shaken drink.” With convenience and cost coming ahead of quality, gum syrup also fell by the wayside.

Rowley also theorizes on another potential culprit — an inability to obtain the actual gum arabic. “This is just spit balling, but I would look at a supply chokehold,” he suggests.”I wonder whether World War I interrupted the supply coming from Africa and India through Europe.”

Whatever the reasoning, bartenders of the era turned instead to simple syrups and stuck with them.

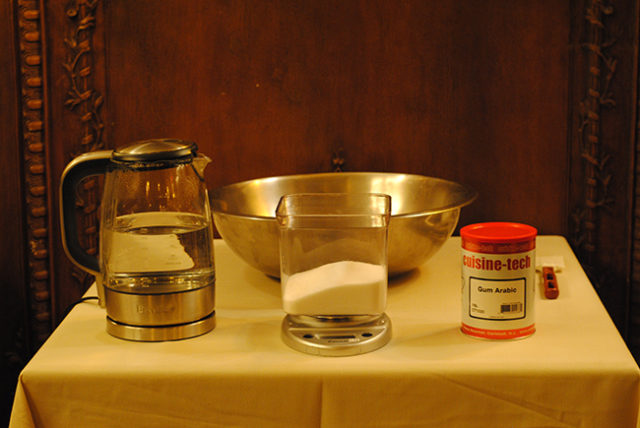

Gum arabic syrup calls for real gum arabic, which is derived of hardened acacia tree sap.

Gum arabic syrup calls for real gum arabic, which is derived of hardened acacia tree sap.

Making Gum Syrup

Rowley’s book is based on a bootlegger’s handwritten notebook jammed with recipes and techniques of the times. Yet, even with this authentic pedigree, he still does acknowledge one point. “I’m guilty of this as well,” he says with another laugh. “I don’t include the almonds. I should have.” The traditional recipe he provides for gum syrup is as follows:

- 2 ounces/55 grams gum arabic

- 6 ounces/180 milliliters water, divided

- 12 ounces/340 grams superfine sugar

Combine the gum arabic with 2 ounces of water. Stir and cover in a small container. Let it sit for 48 hours or until the gum arabic is dissolved. Then combine the sugar and remaining 4 ounces of water, and heat in a small saucepan until the sugar begins to dissolve, before folding in the gum arabic mixture. Remove from heat, let cool and bottle.

Rowley has one final tip on using gum syrup. “You need to have a more restrained hand with gum syrup than you do with simple,” he says. “I think it’s easy to overdo gum, and get something that’s too slick… So a light hand would serve well.”

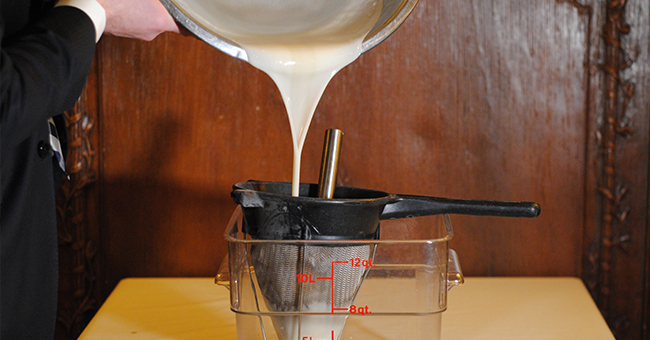

At Betony, head bartender Nicholas Alexander deploys their housemade gum syrup in their Pisco Sour, as well as other egg white sours, and a range of both highballs and stirred drinks. Here’s how they produce their particular recipe for gum syrup:

- 750 grams sugar

- 500 grams gum arabic

- 400 grams water (plus more as needed)

Whisk together the sugar and the gum arabic. Bring the 400g of water to a boil, and slowly stream into the sugar, whisking constantly. Add more water to reach 52° brix. Chill over an ice bath, and reserve in the cooler for service.