When Prohibition finally became the law of the land on January 16, 1920, it was not a sudden shift in attitudes, but the result of a long campaign. The battle between Wets and Drys had been waged fiercely for decades, involving a host of other issues that are hardly far away from our own political battles: immigration, women’s rights, government corruption, and the role of religion in public life. In an age before television and radio, Americans formed their views and took sides under the influence of newspapers and magazines, which were peppered with cartoons and caricatures poking fun at the powerful, and which could sway opinions decisively with a few skillful strokes.

In the late 19th century, the cartoonist Frank Beard (not to be confused with ZZ Top’s ironically clean-shaven drummer) was among the most influential of those illustrators. He was a committed “Dry,” whose images of seedy tavern owners, corrupt officials, and neglected children gave the Prohibition movement a moral force and an instant visual power.

Born in 1842 in Cincinnati, young Frank was the child of a newly visual world, and the comics and illustrations that had begun to saturate the popular press captivated him. Late in life he recalled the thrill of receiving a new comic at Christmas with his brothers: “We would spread it on the floor and lie flat on our stomachs, studying the pictures and spelling out the titles and jokes beneath them, for hours together.” Almost entirely deaf from birth, Beard found his voice in reading and drawing cartoons, publishing his first illustrated jokes as a schoolboy, and going on to publish in the widely circulated comic paper “Yankee Notions” while he was still in his early teens.

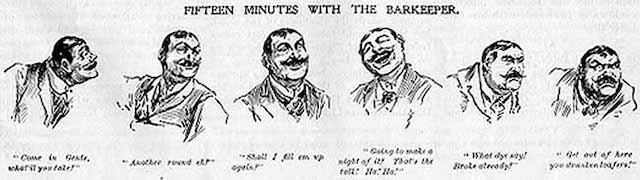

Frank Beard’s catalog of comics includes images of sloppy drunks, red-faced politicians, and the bartender who quickly turns from your best friend into your fiercest enemy like “Fifteen Minutes with the Barkeeper,” above.

Frank Beard’s catalog of comics includes images of sloppy drunks, red-faced politicians, and the bartender who quickly turns from your best friend into your fiercest enemy like “Fifteen Minutes with the Barkeeper,” above.

When the Civil War broke out, Beard’s poor hearing barred him from military service, so he became an army sketch artist, sending scenes of life behind the lines to publications like “Harper’s Weekly.” After the war he established himself as a caricaturist, political cartoonist, and editor, taking over the Methodist weekly paper “The Ram’s Horn” in 1890. There, he took aim directly at the secular decadence of American culture during the Gilded Age.

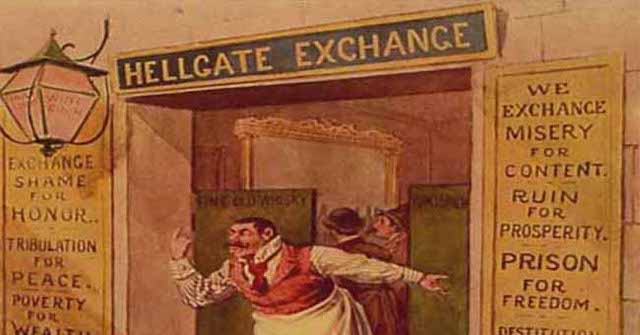

Beard saw no reason why a high moral message should be incompatible with funny, lively, and skillfully drawn illustrations. As the introduction to a collection of his best pictures put it, quoting the Methodist leader Charles Wesley: “‘There is no reason why the devil should have all of the best tunes,’ and it is equally hard to conceive why he should have all of the best pictures.” His cartoons had a liveliness that made them instantly appealing, and could range widely in tone, from highly sentimental depictions of vulnerable women and children, to comic images of sloppy drunks, red-faced politicians, and the bartender who quickly turns from your best friend into your fiercest enemy (as in “Fifteen Minutes with the Barkeeper”). Among his most impassioned targets were the saloon-keepers who enticed vulnerable young men into their lairs, desperate for new blood to replace those they had already destroyed. A cartoon called “Protect that Boy” depicts a sweet-faced boy in a new suit and hat beset on all sides by leering older men who tempt him with gambling, dancing, cigarettes and “racy photographs” — all, the caption explains, gateway drugs. “Therefore, the rumseller goes in league with the seller of cigarettes, and base literature, and evil pictures, and questionable games and entertainments… Every avenue through crime and vice leads at last to the open saloon.” In this way, Beard’s illustrations represented the liquor trade and the effects of drinking in similar ways to modern anti-drug campaigns: the trade presents a friendly face but is violent underneath; it’s a seedy racket dedicated only to grabbing as much money and power as possible; and drinking is a “slippery slope” from pleasure to helpless addiction.

“Rescued” shows a child snatched from the saloon by a towering angel.

“Rescued” shows a child snatched from the saloon by a towering angel.

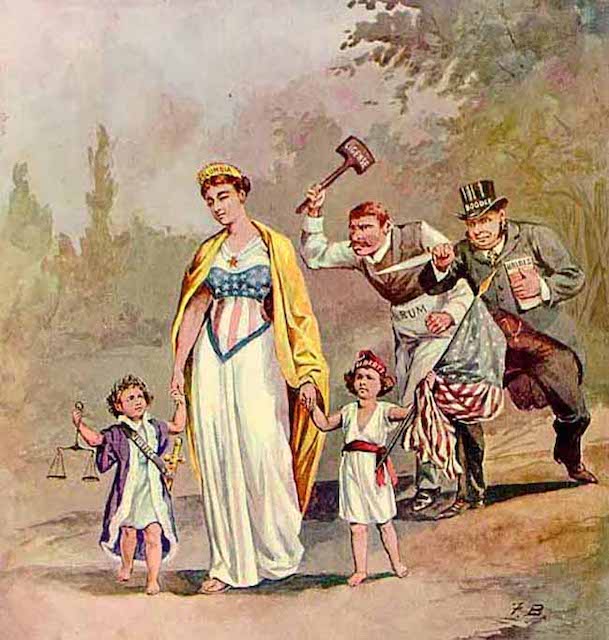

Many of Beard’s illustrations take an explicitly political stance, targeting the liquor trade as an anti-democratic force and a threat to American liberty. “Enemies of the Republic” shows a rum seller and politician waiting to ambush innocent Columbia and her children, Justice and Liberty. Again and again, the cartoons insist that all the supposedly neutral instruments of civil society — police, the law, ministers, local and national politicians — are all actually in the pockets of the saloons, distillers, and distributors of alcohol.

The Anti-Saloon League, formed in Frank Beard’s native Ohio in 1893, was among the most powerful forces fighting back against the proliferation of drinking establishments and their dominance of politics (those “back-room deals” that have come to symbolize secretive, corrupt politics often happened in city taverns). The organization reprinted many of Beard’s pictures in their own propaganda literature, and their side of the fight eventually prevailed in shuttering the taverns and turning off the taps. It’s a shame that the Drys’ witty cartoonist-in-chief died in 1905, too early to see the victory of the cause he held so dear — but nor did he have to witness the disastrous consequences of Prohibition that followed.

“Enemies of the Republic” shows a rum seller and politician waiting to ambush innocent Columbia and her children, Justice and Liberty.

“Enemies of the Republic” shows a rum seller and politician waiting to ambush innocent Columbia and her children, Justice and Liberty.