A whiskey bottle’s label is a memorable thing. We scan shelves and bars for the familiar shapes that adorn our favorite spirits, but rarely do we pause to think why those shapes are there. Noah Rothbaum, an international whiskey expert and spirits writer, has done the digging for us. After years of researching rare whiskeys, earlier this year he released “The Art of American Whiskey,” which examines 100 iconic whiskey labels and their origins. “In many ways,” says Rothbaum, “American whiskey labels are telling the story not just of the whiskey but of America itself.”

Before the 1870s, whiskey was more similar to unregulated drugs like ecstasy or methamphetamines than the amber spirit we drink now. It came not in sealed bottles but in often-homebrewed barrels of unknown provenance, cut with any number of additives and fillers. “There were recipes for ‘whiskey’ that instructed you to mix some other spirit with prune juice and chemicals,” says Rothbaum. Doctors prescribed whiskey as a miracle cure-all but “could never be sure that what they were prescribing wasn’t adulterated,” he says.

Enter Old Forrester, the first bottle-only whiskey, marketed not to drinkers but to doctors. Its advertising? An image of monkeys clambering up the bottle with a corkscrew, trying vainly to tamper with the contents. “It’s a message directly to doctors that this was the real thing,” explains Rothbaum, “there was literally no ‘monkeying around’ with the whiskey.” The bottle’s label details that “there is simply nothing else better on the market,” and if quality meant consistency, that was true.

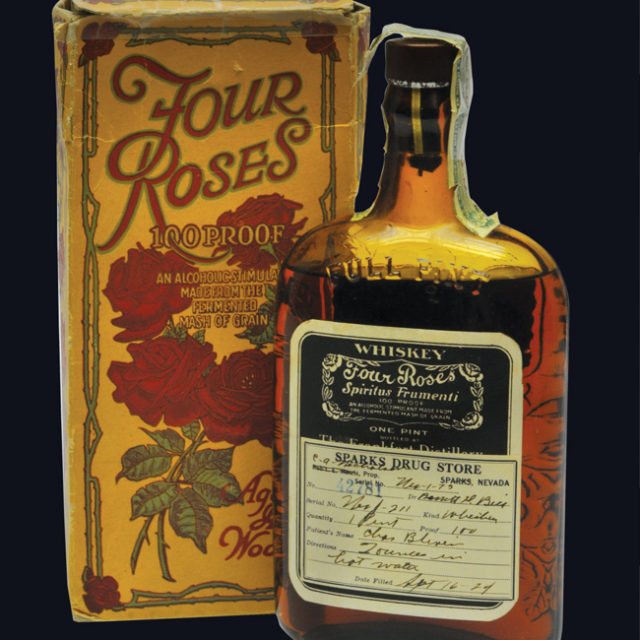

An old-school example of Four Roses packaging. Photo courtesy of Four Roses. Reprinted with permission from The Art of American Whiskey by Noah Rothbaum, 2015. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

An old-school example of Four Roses packaging. Photo courtesy of Four Roses. Reprinted with permission from The Art of American Whiskey by Noah Rothbaum, 2015. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Bottled whiskey was available only for a few decades before Prohibition passed in 1920. Labels changed, focusing on the medical exception for mass-produced whiskey. But many labels made clear distillers knew what customers really did with their product. Golden Wedding Rye is exemplary: the label shows two men in formal dress sharing a glass of whiskey, nary a doctor in sight. There is no mention of medicinal purpose or health benefits. Even more telling is the packaging: Golden Wedding came in an ornate box featuring a couple at the altar, surrounded by gold details and flowers. “The bottle and the packaging design are so beautiful and stylized” says Rothbaum, “it’s clear this is a spirit intended for celebratory purposes and isn’t medicinal.”

Once Prohibition ended, labels changed little save for removing references to medicine. As always they emphasized authenticity through history: pastoral Southern scenes, references to aging. When the social upheaval of the 1960s hit, “the spirits industry [struggled] with a generational gap,” Rothbaum says. “Younger generations didn’t want to be identified with their conservative parents.” But distillers still had to sell whiskey to drinkers of all ages, and the labels they chose evidence an identity crisis.

During this period, Jim Beam literally split its labels between old and new. Rothbaum points to two bottles custom-made for restaurants that carried Beam. On both the top half displays a crest surrounded by corn stalks, with “Beam’s Private Stock” stamped in old-timey block letters—a testament to Beam’s long tradition of distilling. But the bottom half is pure ‘60s kitsch: one label displays a drawing of the mid-century modern La Posada Inn; the other, “Kung Pei Cocktail Lounge” in a dated, faux-Chinese font. “They’re just very odd labels,” laughs Rothbaum. “You can see them struggling to look modern and also very old at the same time.”

Whiskey barely survived this “dark period” of the 70s and 80s, but we’ve come out the better for it. Labels and the bottles they adorn are more diverse than ever, sometimes taking inspiration from the history of the spirit and just as often trying to draw shelf attention with unusual shapes and label placement – what Rothbaum calls the “flashy, sexy” method. But even these continue the decades-old tradition of paying homage to the spirit’s beginnings. “Everyone is into artisanal and craft products now, so it’s no surprise distilleries are going for throwback,” Rothbaum concludes. “It gives people that same, immediate sense of old-style authenticity.”

Noah Rothbaum’s book explores the history of whiskey labeling, and how it tells the greater story of America’s relationship with spirits.

Noah Rothbaum’s book explores the history of whiskey labeling, and how it tells the greater story of America’s relationship with spirits.