For a small Southern city, often known by its tongue-in-cheek nickname “Slowvannah”, Savannah has turned itself into a culinary destination. Charleston landmarks Husk and Prohibition have recently opened the doors to new Savannah locations, and Mashama Bailey’s work at The Grey has had critics across the country praising her take on Port City Southern food. While this host of new restaurants has heralded in new, innovative bar programs, like Kevin King’s local-forward menu at Husk and The Atlantic’s dizzying selection of world wines, the city is not new to the cocktail scene in the slightest.

While prohibition era has long since ended – and thankfully so – the fallout of the era is still ever present in Savannah’s current cocktail culture. Due to the state’s saturation of strict Baptists, Georgia was the first state the country to turn teetotalling into hard law. The first attempt by The Georgia State Temperance Society to ban distilled liquor in the State was in 1836, and while that attempt was unsuccessful, the first Statewide prohibition went into effect in 1908, years before the rest of the country followed suit. While Georgia was at the forefront of the anti-booze efforts, Savannah was having none of it. The sleepy little city was so against giving up their libations that Savannah attempted to secede from Georgia and form its own state, where alcohol would be plentiful.

When seceding was unsuccessful, Savannah became the unofficial headquarters for illegal imbibing. Caity Hamilton, Assistant Director of the American Prohibition Museum in Savannah, explained, “[Savannah]’s location was perfect for moonshining, rumrunning, and receiving bootleg. Moonshiners would make the bootleg liquor in the marshes, where it was easy to hide the stills, then they would run it through the narrow waterways out to the ocean and make a run for the international water line about 3 miles out. They would also make pick-ups in international waters and then rush them back to waiting cars in the marsh.” Al Capone looked to Savannah garage owner Sherman “Moose” Helmey to make his rum-running cars, adding secret compartments and adjusting the suspension to make the car appear to be running light with a full load.

Capone wasn’t the only one with the entrepreneurial spirit – “The Savannah Four are possibly the most infamous bootlegging ring, made up of Fred Sr., William, Carl, and Fred Jr. Haar.” Hamilton storied, “They sold bootleg liquor from their grocery store during statewide Prohibition; National Prohibition made them even more successful. They controlled of a fleet of ships that ran loads of booze from Scotland, France, Cuba, and the Bahamas; once shipments were brought ashore they were broken down and run by road, typically in trucks disguised as potatoes, or in faux oil tankers.” In the day, locker clubs were the place to wet your whistle within the eye of the law. In any of the 147 locker clubs that the city boasted, members would pay to have a ‘storage locker’ where they, through a loophole in the law, could legally store alcohol in a club.

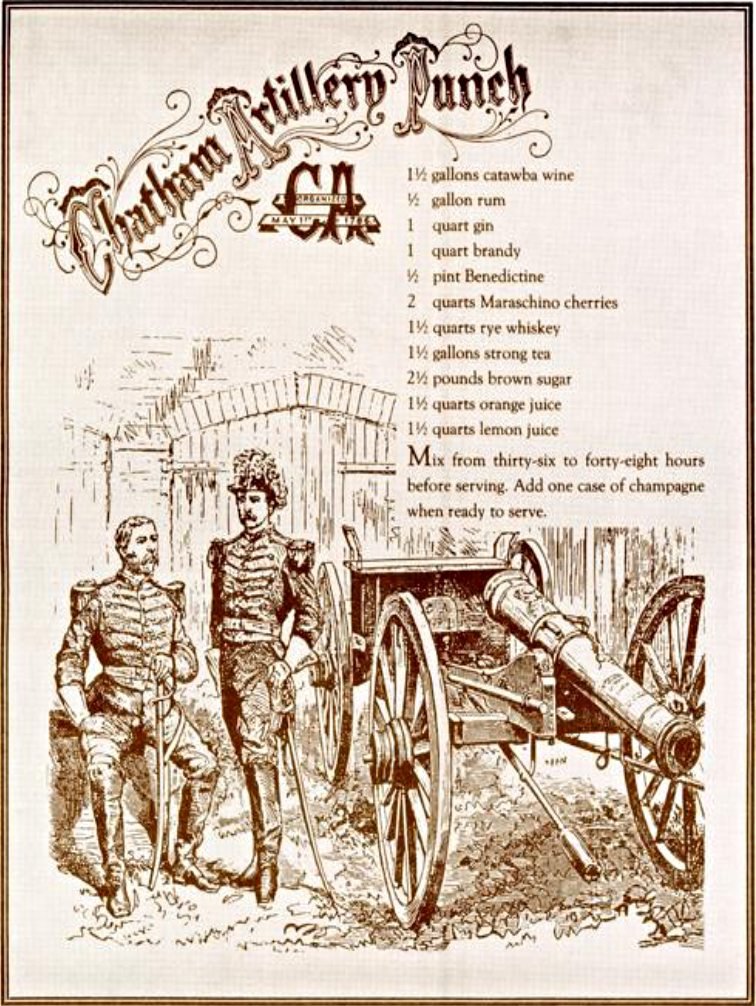

An early recipe for the Chatham Artillery Punch

An early recipe for the Chatham Artillery Punch

One of the city’s most historic cocktails is The Chatham Artillery Punch was first mixed in 1792 and aptly named “killer of men”. In celebration of George Washington’s arrival at the Chatham Artillery. soldiers filled a horse bucket to the brim with crushed ice, rum, gin, brandy, brown sugar, brewed tea, a blend of citrus, and, as that wasn’t enough, an entire case of champagne. As per folklore, after a night of revelry fueled by this beverage, George Washington’s hangover was so treacherous he vowed to never step foot on Savannah soil again (and he didn’t). More recently, The Grey’s former bar manager Cody Henson crafted a less pernicious recipe for the tradition champagne punch and kegged it, doling it out at community events.

Bathtub gin at The American Prohibition Museum

Bathtub gin at The American Prohibition Museum

As much as alcohol was outwardly nonexistent in the city, prohibition was fuel to the fire for the city’s bartenders, pushing them to get creative with ingredients like bathtub gin and marsh-made moonshine. Kevin King, Bar Director at Husk’s Savannah outpost, explained, “Cocktails actually thrived during prohibition because they were a way to mask the flavor of that cruel bathtub gin your neighborhood speakeasy was serving up.” In a cheeky play on the bathtub gin which thankfully, is no longer present on many menus, the speakeasy-influenced bar in the American Prohibition Museum serves up a gin-based cocktail, served in a mini bathtub.

There’s a fetishism to the prohibition era, which is understandable when you think of the draws of velvet lined banquettes in password-kept clubs, with carefully-concocted cocktails you sip while being lulled into happiness by a jazz singer. Many a locale in Savannah channels that fetishism, like Mata Hari and Prohibition. Mata Hari is a speakeasy in its truest form. Head down a cobblestone alley to an unmarked door and utter the password to a man behind a sliding panel. Nightly jazz singers in full flapper regalia serenade while guests sip house-made absinthe. Over at Prohibition, bourbon barrels and hammered tin ceilings are used as decore, while weekly burlesque shows can be enjoyed while sipping on updated Penicillins and fizzes.

While most local menus channel the boozy side of prohibition, the cocktail menu at Husk channels the agenda of the alcohol abstainers. While the menu is host to classic and original concoctions, it’s King’s “Amendment XVIII” section of the menu that really stands out. In a nod to the law that set prohibition in motion, King created a series of alcohol-free cocktail using house made bitters and cordials from seasonal, local produce, like the Lady Delicious, with Pink Lady apple juice, Meyer lemon, star anise, and apple skin salt, and the Sunrise in Antartica, with winter citrus, orange Nehi, cardamom, and rosemary. “We take these just as serious as we would any other alcoholic beverage,” King explained, “We take great care in crafting a unique libation that a non-imbiber can enjoy so they can have a full Husk experience.”

Prohibition-era tipples at Husk Savannah

Prohibition-era tipples at Husk Savannah

A city steeped in history, it’s hard to go anywhere in the city without feeling the city’s storied past – thanks to strict historical preservation laws, most homes in downtown’s historic and Victorian districts are, well, historic and Victorian. Even the city’s businesses have a story behind them – many restaurants within the city’s borders were opened in a repurposed building. The Atlantic, a neighborhood-forward restaurant that boasts an expansive wine cave, took over an abandoned gas station. The Gryphon Tea Room was once a 1920’s apothecary, and the interior shows off the original stained glass and woodwork. The Grey, touted as Eater’s top restaurant of 2017, inhabits what once was a segregated Greyhound bus station. Savannah’s cocktail culture reflects the city’s love of “everything old is new again”. With a history as colorful as Savannah’s, it feels only fitting that the city’s imbibers pay homage to Savannah’s liquid past.

“J&T” which stands for Juniper and Tonic, a play on a Gin and Tonic, garnished with foraged juniper and lime wheel. Photo: Mike Schalke

“J&T” which stands for Juniper and Tonic, a play on a Gin and Tonic, garnished with foraged juniper and lime wheel. Photo: Mike Schalke

“Sunrise in Antarctica” garnished with local kumquat w/ leaf and rosemary from our porch. Photo: Mike Schalke

“Sunrise in Antarctica” garnished with local kumquat w/ leaf and rosemary from our porch. Photo: Mike Schalke